B

blase6

Guest

I am starting this thread because at least one person here doesn’t get how people are moved to act.

I will start with the self-evident fact that: No agent can act without a motive. It is logically impossible. God does not act for no reason at all, he acts out of motivation by his good nature. The rock does not move for no reason at all, it moves because something else pushed it. You do not go buy a candy bar for no reason at all, you buy it because you felt like there was some reason to.

So before any decision made by a person to act, motives must present themselves to the awareness of the person. I cannot choose to buy a candy bar if the knowledge of that option never presents itself to me. If the motives arise simultaneously, to buy a candy bar, to buy coffee, or to not buy anything, then the subsequent actions based on those motives become feasible choices for me.

This is all logically sound, right? Let me go on:

When a person is presented with conflicting motives in a situation, then they begin to consider how to act. For example, I may think in favor of not buying a candy bar because I desire to save money, or I may think in favor of buying it, because I like how it tastes. In all of these considerations for the choice to be feasible, it must appear good in some way. Thinking that I should buy the candy bar because I will get sick due to an allergy is not a logically possible consideration to make. There would have to be some foreseen benefit to having an allergic reaction, for me to be able to find it a desirable choice.

So when someone makes a choice, they are acting towards a foreseen benefit from that choice.

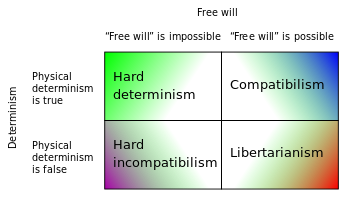

Free will is not necessary to explain this process of making decisions, so it is up to you to show how freedom is more probable than determinism.

I will start with the self-evident fact that: No agent can act without a motive. It is logically impossible. God does not act for no reason at all, he acts out of motivation by his good nature. The rock does not move for no reason at all, it moves because something else pushed it. You do not go buy a candy bar for no reason at all, you buy it because you felt like there was some reason to.

So before any decision made by a person to act, motives must present themselves to the awareness of the person. I cannot choose to buy a candy bar if the knowledge of that option never presents itself to me. If the motives arise simultaneously, to buy a candy bar, to buy coffee, or to not buy anything, then the subsequent actions based on those motives become feasible choices for me.

This is all logically sound, right? Let me go on:

When a person is presented with conflicting motives in a situation, then they begin to consider how to act. For example, I may think in favor of not buying a candy bar because I desire to save money, or I may think in favor of buying it, because I like how it tastes. In all of these considerations for the choice to be feasible, it must appear good in some way. Thinking that I should buy the candy bar because I will get sick due to an allergy is not a logically possible consideration to make. There would have to be some foreseen benefit to having an allergic reaction, for me to be able to find it a desirable choice.

So when someone makes a choice, they are acting towards a foreseen benefit from that choice.

Free will is not necessary to explain this process of making decisions, so it is up to you to show how freedom is more probable than determinism.