Chesterton wrote that in 1925, before most of the archeology had taken place. He may not have known that paintings are often found in caves which show no sign of habitation, as if those caves were set aside (for ritual purposes or just as galleries).

I think he does show signs of knowing that. For example, he says, The [cave] pictures do not prove even that the cave-men lived in caves… The cave might have had a special purpose like the cellar; it might have been a religious shrine or a refuge in war or the meeting-place of a secret society or all sorts of things.

source

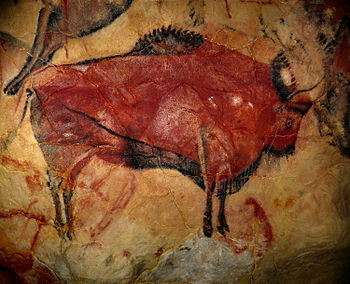

Some paintings show great artistry and intellect, especially given the primitive materials available

I think Chesterton also appreciates this. Speaking of the cave drawings, he says: [T]hey were drawn or painted not only by a man but by an artist. Under whatever archaic limitations, they showed [a] love of the long sweeping or the long wavering line which any man who has ever drawn or tried to draw will recognize… They showed the experimental and adventurous spirit of the artist, the spirit that does not avoid but attempts difficult things…[like] the action of the stag when he swings his head clean round and noses towards his tail, an action familiar enough in the horse. … In this and twenty other details it is clear that the artist had watched animals with a certain interest…

source I think Chesterton’s thinking is quite interesting in how it anticipated modern theories before modern times. Or perhaps others in his time thought the same thing, though he seems to say that most others conceived of cavemen as more barbaric than he thought the evidence warranted: We are always told without any explanation or authority that primitive man waved a club and knocked the woman down before he carried her off. … In fact, people have been interested in everything about the cave-man except what he did in the cave. Now there does happen to be some real evidence of what he did in the cave. It is little enough, like all the prehistoric evidence, but it is concerned with the real cave-man and his cave and not the literary cave-man and his club. And it will be valuable to our sense of reality to consider quite simply what that real evidence is, and not to go beyond it. What was found in the cave was not the club, the horrible gory club notched with the number of women it had knocked on the head. … They were drawings or paintings of animals.

source Another good quote is this one: [A] a little while after [the cave paintings were found], people discovered not only paintings but sculptures of animals in the caves. Some of these were said to be damaged with dints or holes supposed to be the marks of arrows; and the damaged images were conjectured to be the remains of some magic rite of killing the beasts in effigy; while the undamaged images were explained in connection with another magic rite invoking fertility upon the herds. Here again there is something faintly humorous about the scientific habit of having it both ways. If the image is damaged it proves one superstition and if it is undamaged it proves another. Here again there is a rather reckless jumping to conclusions; it has hardly occurred to the speculators that a crowd of hunters imprisoned in winter in a cave might conceivably have aimed at a mark for fun, as a sort of primitive parlor game.

source

This Wikipedia article has a number of references you might find useful on religion.

Thank you.

You’re right that as the evidence is sketchy, in the end you have to look at it for yourself and make up your own mind. For instance when “grave goods” (supplies and artifacts) are found buried with someone, it seems reasonable to infer a belief that they were needed for the afterlife, but you may disagree.

No, I think that’s reasonable enough. But though that suggests to us that they believed in an afterlife, it doesn’t show us that they disbelieved in God, and for myself, I would count it as evidence that they did.